I did my math right

Thoughts on how to motivate students (and all of us) to be excited about math

“Girls are just not as good at math as boys are.”

“Girls are just not as good at math as boys are.”

As a young girl, the statement above was not uncommon whenever adults around me discuss the topic of mathematics. It was the go-to explanation for why so-and-so received the Best in Math award at school and not the other person. It was also one of their explanations why I could not solve math problems as fast as others in class.

The good news was, it definitely became an early lesson on humility. At a young age, I learned that I will never be the best on everything (or anything, really) I want to be good at, but I could always try. And, I did try my very best. The curious thing was, I never did consider myself that good at it. I just thought I understood it just enough to get good grades at school.

What people did tell me was that I was good in the sciences and I had a good grasp of the English language. These beliefs of what I was good at and what I was not too good at factored into my decision of what I should pursue as my college major. For obvious reasons (back then), any field in engineering was an automatic no. So, the boxes for all engineering majors were left unchecked in my college applications.

And, yes, anything in the sciences was supposed to be better for me because I was already good at it. The odd part was that, Psychology was not considered “science enough” either.

So, what’s a girl gotta do? I majored in Psychology anyway. Then I came face-to-face with applied maths and applied sciences that combined both together. Surprise! Surprise!

Fast-forward to my year-long internship as a doctoral student. The most common title for the career field that I am in now had the words “engineer” and “scientist” in it. I guess, I ended up good enough at both anyway.

The most common title for the career field that I am in now had the words “engineer” and “scientist” in it. I guess, I ended up good enough at both anyway.

In the last few weeks, I have been crafting creative lectures to explain scientific concepts to non-scientists and I poured a lot of energy in making the lessons bite-sized and relatable to their day-to-day. Relevance to the students’ daily interactions would make complex concepts easier to grasp. It allows for the terminologies associated with the topic to be part of their regular conversations. And, the most important part of it is that, topics that used to be thought of as impossible to grasp are suddenly within their reach.

People’s brain work differently from one another. We have different learning abilities. So why should concepts be taught uniformly across such variations in our ability to learn? Simply put, if we only use one method of teaching and that chosen method is only effective for a portion of the class, then we are giving that portion an unfair advantage while excluding the rest from the joy of learning. The rest of the class would end up being categorized as “not as good” because the method of teaching does not quite fit the way their brains work.

When I was in high school, Physics was my favorite subject. Oddly enough, I would sometimes get deductions from my test scores because I did not quite follow the steps to solve the problems exactly as prescribed - even though I arrived at the right answers anyway. This was a consistent problem for me throughout my basic education years.

Let me tell you how I solved math problems correctly without following the prescribed steps: I drew the problem to arrive at the solution. I attached the numbers onto my drawings, then started solving.

In graduate school, mathematics took an applied form in quantitative methods. When we studied regression models in class, I drew them in my notes and I visualize them that way in my brain too. My classmates would often ask to borrow my notes and photocopy it. At the end of the two semesters, my classmates even gave me an award for it (we all got our unique awards for how we performed/not performed in class). 😊

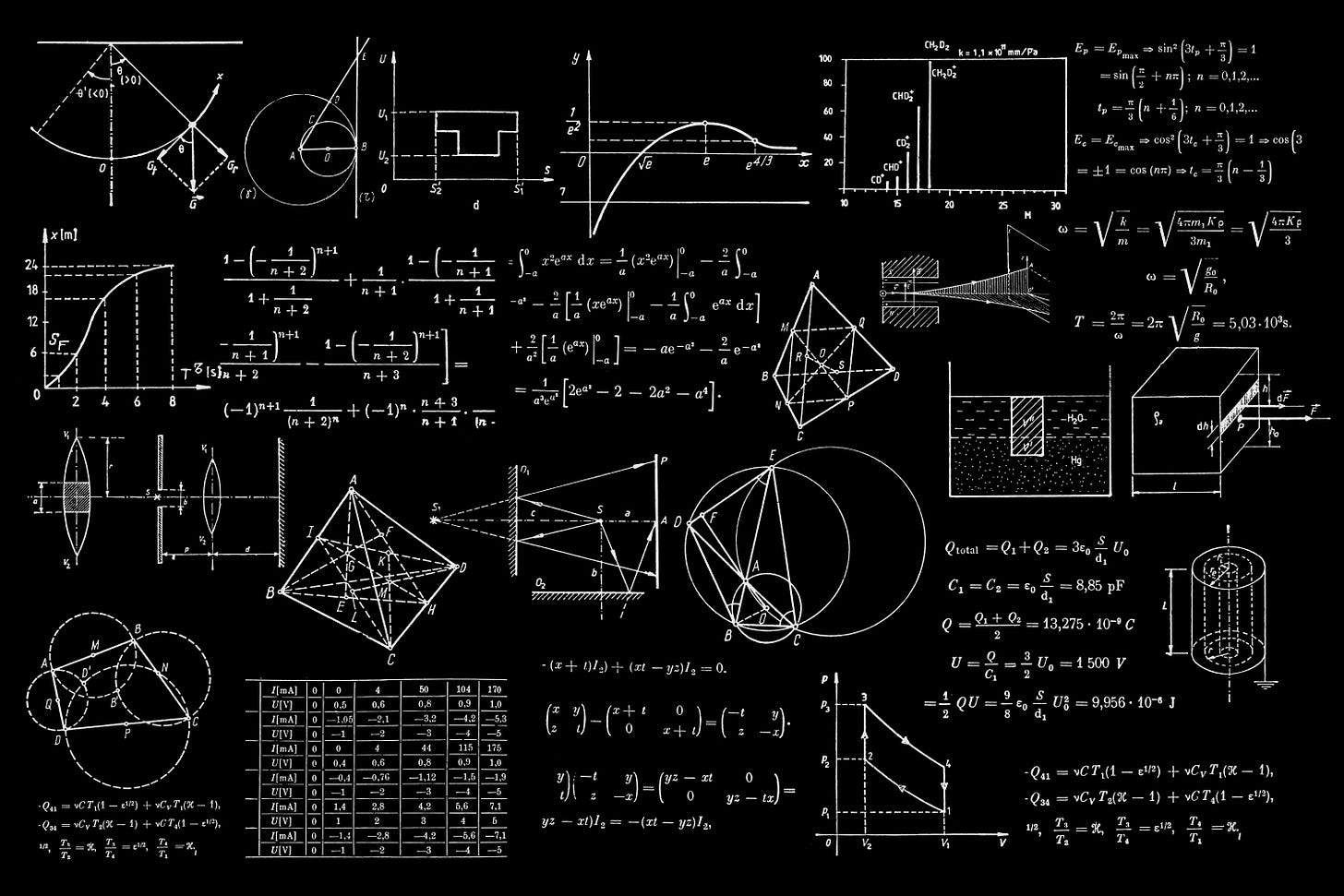

Now that I am older (and hopefully, wiser), I realize that there are actually a lot of concepts in mathematics, sciences, and in their respective applied fields that are represented visually. In short, there was nothing wrong with how I learned things.

For example, in statistics, measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode) can be understood with the image of a curve (a hill or mountain ⛰️ in my imagination). The shape of the curve would tell us a lot about the data even without having to look at the numbers right away. Kurtosis would be indicated by how high the peak is and the thickening of the tails. Skewness, on the other hand, would be indicated by which direction (left or right) does the tail point to.

Do not even get me started about visualizations for correlation. Isn’t it fascinating to know that one can identify if it is a high, low, or moderate correlation and whether it is a positive or negative correlation by merely looking at the pattern of the dots on a scatterplot?

I have so much more examples for how complex concepts that seem to be too intimidating to understand at first could potentially be grasped much readily if only they are explained in a much friendlier way.

The point of this post really is…

This is my long-winded and very nerdy way to encourage my nieces and nephews to use their imagination when learning. While I am certainly advocating for you to listen to your teachers and follow their instructions (wag pasaway!), I am also nudging you not to shy away from using your imaginations to find the best way to understand concepts. Many things are hard to understand when they are foreign and new. The important thing is you do not stop learning at the first sign of difficulties. If you failed the first time, try again. But the next time you do, try to use a different tactic. In that process, do not forget to use your imagination and creativity too.

Do not ever think that you can escape mathematics or any of the sciences in your lifetime. The only choice you have on the matter is how you will learn them and use them to your advantage.

Lastly, do not ever let anyone tell you (not even yourself) that you are not good at math. When all other reasons to convince you fail, you can always fall back on the knowledge that a certain percentage of your genes match mine. 😉

great post.How empowering.

It always amazes when a teacher in elementary or even high school does that! The kid is IN SCHOOL TO LEARN! That teacher has now given that kid an excuse to wonder why they are in school! Maybe make them hate it because they are so dumb…see where I’m going here…my grandson has adhd and the teachers seem not to care and guess what…HE HATES SCHOOL, EVERY PART OF IT, EVEN RECESS! Great article!